Resonance Over Reach: Part 2—The 3 Pieces of a Clear, Memorable, Differentiated Message

⏪ Last time, in part 1, I wrote about how to connect with your audience without shouting into the storm by turning your expertise into an influential idea. Read more about premise development and the XY premise pitch.

⏩ Today, in part 2, how to message your premise in a way that gets buy-in from others and helps earn trust more quickly...

"Oh gross," was my first thought, followed by, "Awww, adorable."

My six-year-old and I had just arrived at the New England Aquarium, where we rushed up to our favorite exhibit. Inside the building, rising several stories high, sits a massive tank of ocean creatures. Around this cylinder of sparkling blues and greens, snaking upward to the very top, is a platform of gray carpet. Every few feet, you can take a break from your climb and gaze into the tank.

Aria rushed up to the first window and smushed her hands and face against the glass. I immediately had the same dual thought most parents have when observing their kids. At the very same time, I was in awe of this child's wonder at the world, and I was so grossed out by the idea that she was basically licking a public display.

Aria peeled herself off the glass and looked at me.

"DAD-dee," she said in the musical way she speaks. "Why do we have aquariums?"

This is the kind of question I wasn't prepared to answer as a parent (12 times a day). Before becoming a dad, I knew I'd get pelted with the simple stuff ("How do I zipper this?" ... "What's that animal called?") and I readied myself for the complex ("Why is the sky blue?" ... "Where do babies come from?") What I didn't realize is there's a third category of questions you're asked. It's not difficult or dense to answer, nor are you concerned with sharing too much technical or mature information for your child. Instead, these questions require a kind of thinking on behalf of your kid which I can only describe as "multiple move thinking." You'd LOVE to find that one perfect line that sums up everything they'd need to know, but you end up speaking in paragraphs or even pages of information, hoping they'll understand and care.

Sound familiar?

I thought to myself, "How in the world do I answer this question?" Why do we have aquariums? I gave it a shot. I said to Aria:

You know how we want to protect animals and the ocean? ("Yeah!")

So to do that, we need to get lots of people interested in that. ("Okay.")

And our hope is when lots of people see these animals up close at the aquarium, they love them and want to do things to help them. Maybe they donate money to science or volunteer their own time, maybe they vote in elections for people who will protect the ocean, or maybe they become scientists themselves!

Aria thought for a moment, a tiny piece of pink coral backdropped by a shimmer of fish.

"DAD-dee," she said slowly. "When I grow up, I want to be an underwater scientist-teacher who tells stories and sings songs and helps people and animals."

Matter of fact. Just like that. She understood what I was saying. She cared about my words. She was ready for action.

* * *

I won't lie. I was proud of myself that day. Huge parenting win. I also realized that this is how we need to get kids to understand and care about most things. We can't just shove a bunch of facts at them or explain things paragraphs-and-pages at a time. Instead, we need to secure little moments of agreement from them, beat by beat.

You know how we want THIS? ("Yeah!")

Well, that means we need THIS. ("Okay.")

And our hope is that it all leads to THIS. ("I'm in! I'll be an underwater scientist-teacher who tells stories and sings songs and helps people and animals!")

The thing is, that's not only how we get kids to understand and care. It's how we get people to understand and care too.

We want.

We need.

We hope.

First, we have to align with them and secure one small, easy moment of agreement. Then, we can tell them what we need to achieve that—something we likely already knew, given our area of expertise and/or business offerings. Finally, we can show them where this might lead us, if we actually did what we need.

We want.

We need.

We hope.

It's kind of shaped like a ladder. We need people to move down the ladder, from the superficial or initial understanding of our ideas or relationship with us to deeper understanding and deeper connection.

I realized back then, wait a second, I do this with my own message all the time.

We want: Don't market more. Matter more.

You're out there marketing. You're probably looking for ways to market more, or at least being told you need to do so. You wish your marketing mattered to others. You want to matter more. (That's an easy first moment of agreement, an easy and critical first instance of alignment between you and me. So I can continue speaking.)

We need: Think resonance over reach.

That's my premise for my entire business and public platform. That's the assertion I defend about a topic I explore (marketing), which aligns all my choices and informs my reputation. As the core idea informing the rest, "resonance over reach" is what I think people need to embrace to communicate in ways that actually connect and cause others to pick you, stick with you, remember you, and refer you, despite the odds.

Our hope: Be their favorite.

I love to tell the world, "Don't be the best. Be their favorite." That's our hope, our grand aspiration. That's the best-case outcome if we actually resonate deeper and more consistently: we become their favorite. That's the most defensible status we can possibly attain. No matter the options, no matter the noise, they're going with YOU, not because you spend more on marketing or shout louder or hype harder, but because you resonate deeper.

We want: align with others around their current goals and understanding, shifting their objective ever-so-slightly. Get a first moment of agreement on something they already want to achieve.

We need: assert your premise, that big idea you own in people's minds. It might have been hard to start with that, but it follows logically from the first. Your premise took you awhile to develop. Your perspective, stories, and years of experience all combine into one long journey for you to arrive at that one idea. Your audience didn't go on that same journey. They don't start out caring the way you care, seeing how you see. You have to show up and show them. Logically, if we want the first thing, we need the second thing. That's the best way forward as you see it. Now they're starting to see it too. Finally...

Our hope: aspire them to the best-case outcome of this. Where is this all leading? Where might this take them? What just became possible (and oh-so-desirable) because of your premise?

This is something I call Laddering Down Your Message.

As much as you'd like to deliver one pithy answer, one PERFECT line in response to their questions or needs, it's a fool's errand to search for that. But it's also foolish (if understandable) to communicate in paragraphs or even pages of explanation for why they should care about your ideas and care about you. Maybe we can't communicate in one perfect line, but we can try three damn effective lines, in the right order.

Here are two examples to show you what I mean...

Mykel Dixon is an incredibly energetic and magnetic speaker. He travels Australia delivering keynotes to thousands of people at a time, inspiring them on stage with big ideas, incredible stories, and even music, as he sometimes brings his band on stage with him.

Myke is the author of Everyday Creative: A Dangerous To Making Magic At Work, and he brings his unique brand of magic with him everywhere he goes.

Just one problem.

Everywhere he went, Myke talked about the importance of "the source." He'd say, "It flows through you," like music.

He'd also talk about "wild work," signing off every post and update with the same line: "It's WILD WORK, but someone's gotta do it!"

When people encountered Myke and his ideas, they felt inspired. They felt energized. And they felt ... confused.

Because what does he mean? The source? Wild work? Sounds exciting! Delivered to be exciting too, thanks to Myke's natural ways. But what. does. he. mean?

Myke needed to ladder down his message. In particular, he needed to emphasize the first line of the three rungs of the ladder: what do others want? Can you tie the message to that?

Myke is a natural evangelist. When he tries to resonate with others, he does it by emphasizing his originality. Typically, evangelists try to out-emotion everybody in order to connect, so Myke of course brings a personal POV with him and brands his ideas to be ownable by him ("the source" and "Wild Work").

When an evangelist constructs their message, they need to get better at grounding their ideas in the realities of the audience. These natural big thinkers and emotional storytellers (hi, that's me too) often lack practical, prescriptive advice, almost scoffing at the notion of listing out steps for anyone, while visual frameworks and contextual models are a big need to complement their signature stories and branded terminology. That's what gives the evangelist more well-rounded IP.

For Mykel Dixon, his laddered-down message might sound like this:

1. Align ("we want")

If you want to get ahead, you need to come alive. We think getting ahead means we'll finally feel alive, but we've also felt alive in moments already: the first notes of a song and we're instantly singing and feeling something; the sand on our toes, and we're immediately mindful and peaceful; the work that puts us in-flow, like we're grooving without effort. What is that? It's undeniable. How can we tap that instant aliveness proactively? We keep seeking productivity hacks and best practices to get ahead, when really, we need to find our energy source first to come alive.

2. Assert ("we need")

Your source matters more than their systems. We've all met people who have that energy: the coolest person in the room without forcing it, the leaders we love to follow, the voices who communicate so clearly and easily. They've found a way to tap into their source first. They've come alive already, and as a result they're getting ahead—not the other way around. Knowing what makes you come alive and tapping into that is the difference between decaying towards dull and growing like wild.

3. Aspire ("our hope")

You won't have more work in your life. You'll have more life in your work. It's wild work, but someone's gotta do it!

Now it makes much more sense, and Mykel can refine and modify this language to both improve over time and flex into any need he has: website copy, keynote speech, social media presence, pillar projects, sales process, and more.

Our other example is Alison Coward, founder of Bracket, a firm which helps strengthen and future-proof team cultures. Unlike Mykel Dixon, Alison is comfortable speaking in statistics, as she often shares research and talks about trends in collaborative work and team-building. She doesn't cite new terms like "the source." Instead, she talks about phrases others readily understand but perhaps poorly execute. She's the author of the book Workshop Culture: A Guide to Building Teams That Thrive, and her speaking feels like a very smart lecture from a professor, less like a show, as with Mykel. Neither are more worthy, but we need to know who we are and what that means.

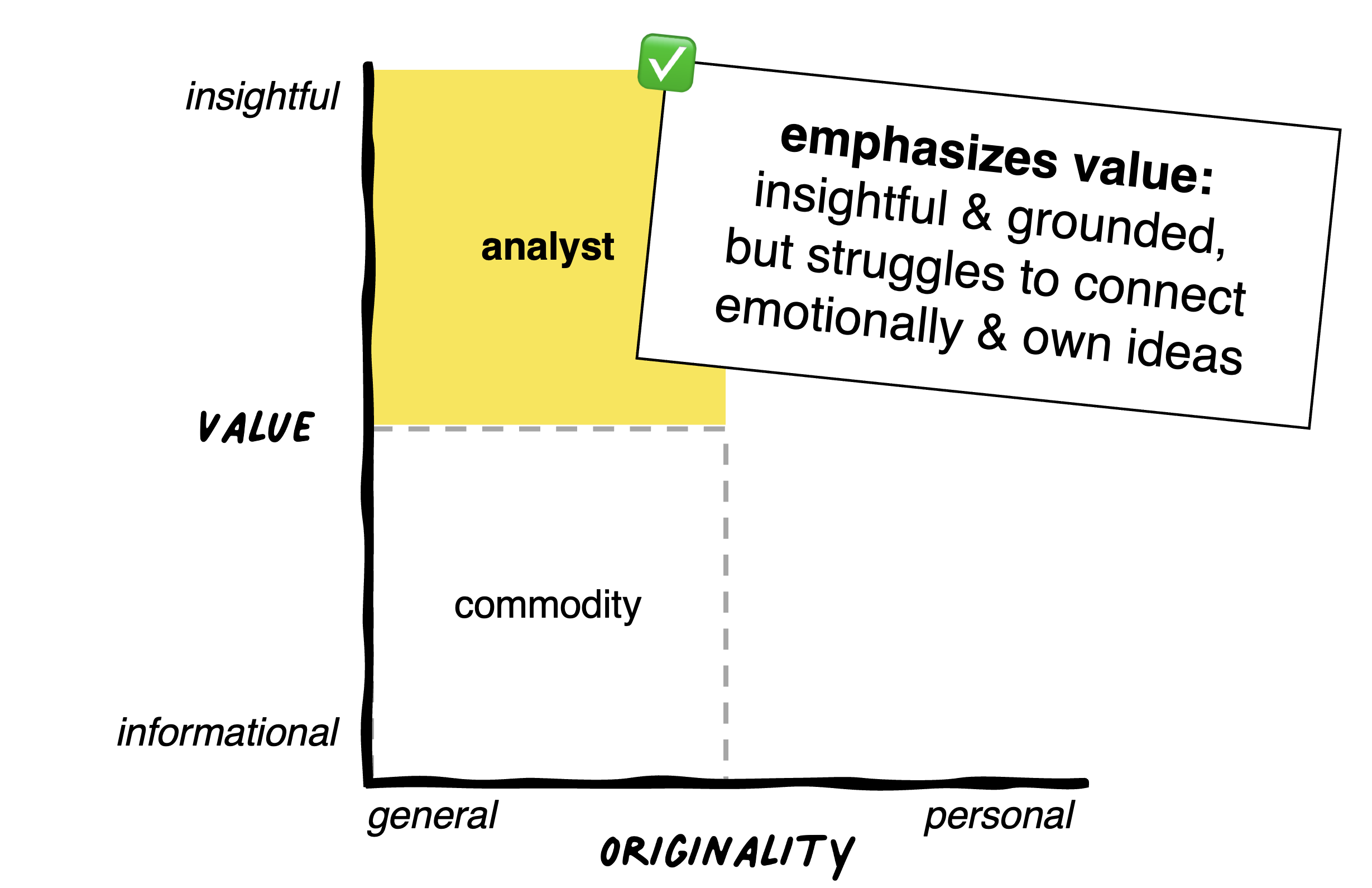

What this means: Alison is a classic analyst. When she tries to resonate with others, she does it by emphasizing her value to them. Typically, analysts try to out-expert everybody in order to connect, so Alison of course brings an insightful and grounded approach to communication and teaching, but she might struggle to connect emotionally or differentiate with ownable ideas.

When an analyst constructs their message, they need to get better at elevating their ideas to feel more like a profound and enduring change in perception or singular Big Idea, and less a list of bulleted prescriptions. That means the second rung on the ladder is a big priority: can you articulate some kind of bold claim or clear assertion? What do others really need? Say it succinctly, not with pages upon pages of saying, "Well, there are myriad things we could try, and this study says X while that study says Y." No! How do YOU see it, as the leader? While evangelists like Mykel have no issue making these claims, analysts often dilute their message by backtracking from clear, change-oriented claims. They meet others well at the first run ("We want...") but they offer 17 different second rungs to choose from, never arriving at a clear premise for what others need. So analysts need to really focus on nailing the second rung of the ladder.

For Alison Coward, her laddered-down message might sound like this:

1. Align ("we want")

Team-building doesn't happen away from work. It happens as we work. We've all been there: the offsite, the retreat, the trust falls, the team dinner where everyone's supposed to bond. And for a moment, it works. The energy is high, people are laughing, connections are forming. But then Monday morning arrives, and within hours, we're back to the same old patterns—siloed communication, competing priorities, missed handoffs. They're building a team, establishing their norms, but without the lessons or energy from the workshop. They barely had time to think about their core jobs before the time away, and now they're even more pressed for time, thinking even less about things "unrelated" to their immediate success, like team-building. But the team will naturally create habits and norms and processes and behaviors even still ... just not be design.

2. Assert ("we need")

We don't need workshops. We need a workshop culture. In the workshop, they focused on collaborative problem-solving, trust-building, and creative thinking—and that's exactly what they need day to day. Why are we not making that connection as leaders? Workshop culture means embedding the collaborative practices, psychological safety, and shared problem-solving of great workshops into the daily rhythm of work. It's not about eliminating workshops entirely—it's about creating an environment where the team-building, trust-building, and skill-building that currently happens when work is paused can instead become the natural way the team operates.

3. Aspire ("our hope")

The result is your team does the team-building every single day. Workshop culture creates a team of co-creators rather than a traditional hierarchy where the leader drives everything. When teams truly embrace workshop culture, they naturally engage in the behaviors that build high-performing teams: they give each other feedback in real-time, they collaborate on solving problems together, they surface conflicts before they fester, and they continuously improve their ways of working. It's not about adding more to everyone's plate—it's about transforming how the work gets done so that team-building becomes an invisible, constant process woven into every project, every meeting, every interaction. This takes care of the feeling that "I just don't have time for this." Imagine being a leader who no longer needs to manufacture team-building moments because everyone is using the principles of effective team-building while doing the work that matters most.

Ladder down your message. It's not enough to have expertise, you need a distinct premise. But it's also not enough to make a bold claim or share a pithy tagline. You need to get buy-in for your ideas and message your premise, everywhere you go.

Align around a worthy objective they already want to achieve.

Assert a powerful premise which they need to adopt to achieve what they want.

Aspire to a best-case outcome you show them, which you might just attain together if they choose to hire you.

If you want to routinely resonate with others:

Don't talk topics. Own a premise. Give them your insightful reframe on a familiar topic. To help, try the XY premise pitch (see Part 1).

Use your premise to clarify your message. Making it feel personal and desirable to them. You can't tell them to care. You have to show them why they would. To help, ladder down your message.

In the end, we all want our work to matter to others, but we have to package and communicate our thinking to connect. That's how we can stop competing on the volume of our marketing and start leading the way thanks to the impact of our ideas.

Don't market more. Matter more.

Think resonance over reach.

Don't be the best. Be their favorite.